History of The National Energy Authority

Waterfall Committee

Ambitious plans for power generation at the beginning of the 20th century called for a response from the government. In 1917, the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, appointed an inter-parliamentary committee, the so-called Waterfall Committee.It delivered informative opinions and drafted many draft laws on water issues and power plants. The Water Act of 1923 and the Waterpower Concession Act of 1925 were enacted.

In 1929, Jakob Gíslason began working for the government on the planning of power plants and electricity utilities, and in 1930 he was entrusted with the supervision of power plants throughout the country.There was no constant or regular public research in this field until 1932 when the Office of Road Administration was entrusted with a special law to investigate which watercourses would be most suitable for power generation in each part of the country.

The Office of the Government Inspector of Electrical Affairs was created in 1933,on the basis of the Act on Electric Power Plants from 1932, and Jakob was its director. In that job, the actual inspection duties quickly became intertwined with investigating the conditions across the country to obtain, transport, and distribute electricity.

Director General of the State Electricity Authority

Towards the end of the Second World War, it became clear that there was a need for new comprehensive electricity legislation in Iceland. Such legislation came with the Electricity Act no. 12 from April 2, 1946, and Jakob Gíslason was appointed Director General of the State Electricity Authority. This law was the first time that an overall policy on electricity matters in Iceland was agreed upon. One of the most important aspects of a country’s hydropower research is the systematic, continuous measurement of the flow of falling waters, so-called water measurements. 1947 saw the beginning of the Hydrological Services of the Director General, and later the NEA, whose task it was to do such measurements where it was considered most suitable for power generation. They have been ongoing since.

1894

The first water flow measurements in rivers that are known to have been made in Iceland were made by a Norwegian geologist, Professor Amund Helland, in the summer of 1881. The first measurement for an electric power plant was made in the Elliðaá river on October 21, 1894 by Sæmundur Eyjólfsson. However, nothing became of that power plant then. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the engineers Jón Þorláksson and Guðmundur Hlíðdal measured many rivers in Iceland for foreign waterfall associations. Measurements were also done by foreigners on behalf of these associations. Most of the time only individual flow measurements were done, but no continuous measurements over a long period of time were carried out.

1918

In 1918, at the suggestion of the Waterfall Committee, the government commissioned the Director of Roads to take care of water measurements in the country’s main waterfalls. In the summer of 1918, he installed water level gauges at nearly twenty waterfalls. However, budgets were limited. Readings on these water level gauges were continued for several years, and limited flow measurements were made. Several of these gauges were destroyed or measurements stopped for a time, so continuous flow measurements were not obtained.

1944-1960s

The fragmented and limited water measurements continued with the Director of Roads until 1947 when the Director of Electricity took them over. Funding for them was always low and dropped altogether between 1938 and 1943. In the 1944 budget, the State Electrical Authority was allocated money for water flow measurements, which was then transferred to the office of the Director General when it was established in 1947.

The first research of the Director General on hydropower, other than hydrometers, focused on finding promising locations for power stations to provide various parts of the country outside the South-Western corner with electricity, as the Sogsvirkjun hydro power plant was intended to take care of that part of the country. Several preparatory studies were carried out at the Sog river on behalf of the Sogsvirkjun power plant and also at the Laxá river in the Suður-Þingeyjarsýsla region, on behalf of the Laxár power plant.

Towards the end of the 1960s, the aim was for the Sog river to be fully utilized for hydropower generation, and the next hydropower plant site in the Southwest had to be chosen. Hydropower research by the Director General was greatly increased and reached the level it has been at for most of the time since.

Utilization of geothermal energy

The exploitation of geothermal energy did not begin until the old swimming pools in Laugardalur were built in 1910. However, its significant use first began with the drilling of wells at the Washing Pools in Reykjavík in 1928. Following these drillings, the Reykjavík District Heating company was founded. There, research was conducted by Dr Þorkell Þorkelsson, head of the Meteorological Office, but special laws on geothermal heating and geothermal research were enacted in 1940 and 1943, and the National Research Council was then entrusted with managing them. The first survey of Icelandic geothermal energy in the twentieth century was carried out during these years and is still cited in research reports.

Soon after the creation of the office of the Director General, geothermal research was greatly expanded. A special state company, The State Drilling Contractors (later Iceland Drilling), was set up under the supervision of the Director General to handle geothermal drilling. He was also instrumental in the state and the City of Reykjavík working together to buy a large drill rig to drill for geothermal steam, but until then they had mainly been drilling for hot water. This drill arrived in Iceland in 1958 and for a long time it was simply called "The Steam Drill“, but was later called Dofri (from Norse mythology) when another larger steam drill arrived in Iceland in 1975. It was named Jötunn (also from Norse mythology).

The Geothermal Department of the Electricity Authority was established at the beginning of 1956.

The Energy Act of 1967

In the mid-1960s, it was considered timely to review the Electricity Act of 1946. There were two main reasons for this: Firstly, with the establishment of Landsvirkjun, the National Power Company of Iceland, the directive contained in the Electricity Act had changed greatly; and secondly, the Office of the Government Inspector of Electrical Affairs by then carried out much more important and extensive activities than were discussed in that law. The new energy law no. 58/1967 took effect on July 1, 1967. Jakob Gíslason was a member of the committee that revised the law and he was very influential in its drafting. The review was completed in 1966.

The Energy Act deals with both the production of electricity and geothermal energy; electricity, heating distribution, and drilling are all covered. The law also had a special chapter on the Iceland State Electricity Distribution Company, now RARIK. The Office of the Government Inspector of Electrical Affairs was abolished, but a new organization, Orkustofnun, The National Energy Authority (NEA), took over the role of that office, other than that which fell under the auspices of the Iceland State Electricity Distribution Company, which was made an independent organization. Jakob Gíslason was appointed Director General of the NEA as soon as the law came into effect.

In the Energy Act, the NEA is entrusted with the management of the drilling (through the State Drilling Contractors) and the State Geothermal Distribution Organisation, which were created when the silica factory at lake Mývatn, Kísiliðjan, was established. Both companies were run as so-called B-part companies under the leadership of the NEA until Iceland Drilling hf was established in February 1986 and the Geothermal Distribution Organisation was closed at the end of 1986. The State Electrical Authority was then under the supervision of the Director General of NEA until 1979 when it was finally made an independent institution.

According to the law, the Energy Fund took over all the assets of the Electricity Fund and the Geothermal Fund.

Increased activity

Soon after The National Energy Authority started its operations, its research activities began to greatly increase. Most of the projects were related to energy issues, research for hydroelectric power plants and geothermal research for heating utilities and individuals.

The reasons for the rapid growth were many, but mainly it was the growing importance of energy in modern society. First, there was the increased utilization of hydropower for electricity production for general use and for heavy industry. Secondly, a lot of emphasis was placed on the increased use of geothermal heat for district heating due to the enormous increases in oil prices, and, thirdly, there was the direct use of geothermal heat for industry. At the same time, the institute has carried out a significant amount of research on useful minerals and conducts research on cold water for consumption and business operations.

In accordance with this, the institute was divided into two research departments, the geothermal department and the electricity department, as well as the operations and economics departments.

In 1971, a new research department was established at the NEA, the earth survey department, and it was intended to conduct research for the acquisition of potable water and useful minerals. The Energy Act was amended in 1972 in accordance with this. This department was merged with the NEA’s electricity department in 1981 into a new one, the hydropower department.

On the basis of a law passed by Alþingi in the spring of 1985, the company Orkustofnun hf. was established on August 8 of that year. The purpose was to market abroad the knowledge that the NEA possesses in the field of utilization and research on geothermal energy, hydropower and planning in energy matters.

At the same time as the law on Orkustofnun hf. was enacted, an amendment to the Energy Act no. 58/1967 was also enacted to the effect that the minister appoints three people to the board of the NEA for two years at a time. Before, there were no provisions in the law on the management of the NEA, but since 1981, the Minister places it under the supervision of a board of governors.

The picture here to the side is of the first board of the National Energy Authority. The Chairman, Egill Skúli Ingibergsson is in the middle, Kristmundur Halldórsson second from the left and SveinbjörnBjörnsson on the far right, together with the Director General, Jakob Björnsson, on the far left, and the Board Secretary, Páll Hafstað.

Director Generals

The organization that has been described here was mainly valid until the end of 1996. A change of Director Generals occurred in the beginning of 1973 when Jakob Gíslason retired due to age and was replaced by Jakob Björnsson. He held the position for nearly a quarter of a century until Þorkell Helgason replaced him in September 1996. Þorkell held the position until the end of 2007 and at the beginning of 2008 Guðni A. Jóhannesson took over. Guðni retired in the middle of 2021 and Halla Hrund Logadóttir took over.

NEA’s geodetic surveying

Land surveying by the NEA began shortly before 1950. It continued as part of the activities of the NEA in 1967. The surveying activities of the NEA were stopped and data regarding the activity was handed over to the Icelandic Geodetic Survey in 2003.

Turn of the century changes

A significant change in the organization of the National Energy Authority took effect at the beginning of 1997. The purpose of the organizational changes was to separate advice to the government and management of public funds for energy research from the implementation of the research. The research was then carried out in the energy research section of the institute, which in turn was divided into two independent operational units: the research division and the hydrological services division. The other part of the NEA, the energy section, was divided into the natural resources department and the energy management department, as well as the United Nations University – Geothermal Training Programme.

On July 1, 2003, the next step was taken and the research department of the National Energy Authority was completely separated and made into a new organization, Íslenskar Orkurannsóknir, or Iceland GeoSurvey. The Act on NEA and the Act on Iceland Geosurvey were approved by the Alþingi in the spring of 2003. The hydrological services division of the NEA became an independent unit and financially separated from other activities of the NEA. With the Act on the Meteorological Office of Iceland no. 70/2008, the Met Office and the hydrological services division merged into a new organization.

The Geothermal Training Programme

40 years

+ 700 Fellows

Library and Publishing

The National Energy Authority founded and built up a specialist library in energy, resource utilization and geosciences that ran until the end of 2022 when it was shut down. The library served the various departments of the NEA and housed all the reports and other publications published by the NEA, Iceland GeoSurvey and the Geothermal Training Programme. After Iceland GeoSurvey and the GTP moved from the Orkugardur (the premises that housed all these organisations) at the end of 2021, the operational basis for the museum ended and a decision was made to close it. The last director of the library, Rósa S. Jónsdóttir, was responsible for making all the published material of the NEA, Iceland GeoSurvey, and the GTP available in a digital format. A large part of the books and publications went to the National Library of Iceland, and digital versions are available through their search website, Leitir.

Over the years, the National Energy Authority has published a lot of interesting material; articles, maps and various informational publications. They can be found in our Archives section.

Sigurjón Rist’s papers are a collection of more than 300 short reports on water measurements and glacier studies, written during 1947-1966. Most of them are by Sigurjón himself, but there are also articles by other authors. Almost all the submissions are now available electronically and registered in Leitir. There you can search by various parameters, such as author, subject words, titles and place names. The publication Orkumál (Energy Papers) contains statistical information about Icelandic energy issues. They have been published intermittently since 1959. In 2005, the publication was divided into three issues, each of which deals with electricity, geothermal energy and fuel, but from 2007 only issues on electricity were published. It ceased publication in 2010. The NEA has published various interactive map databases on the Internet that are related to the organization’s activities. Some of these systems have either been closed or merged with existing systems. The NEA's current digital cartography databases can be found here. Þorvaldur Bragason was a leader in establishing the NEA’s electronic maps and web view.

New focus

With the appointment of the new Director General, Halla Hrund Logadóttir, new and fresh priorities became focal points for the National Energy Authority and the activities of the organization were restructured. Climate, Energy Transition and Innovation, Analytics and Data, stronger governance, and advice to government, reflect these new priorities. All this is done to help the public, corporations, institutions and the government of Iceland to get a foothold in these transitory times in energy and climate matters.

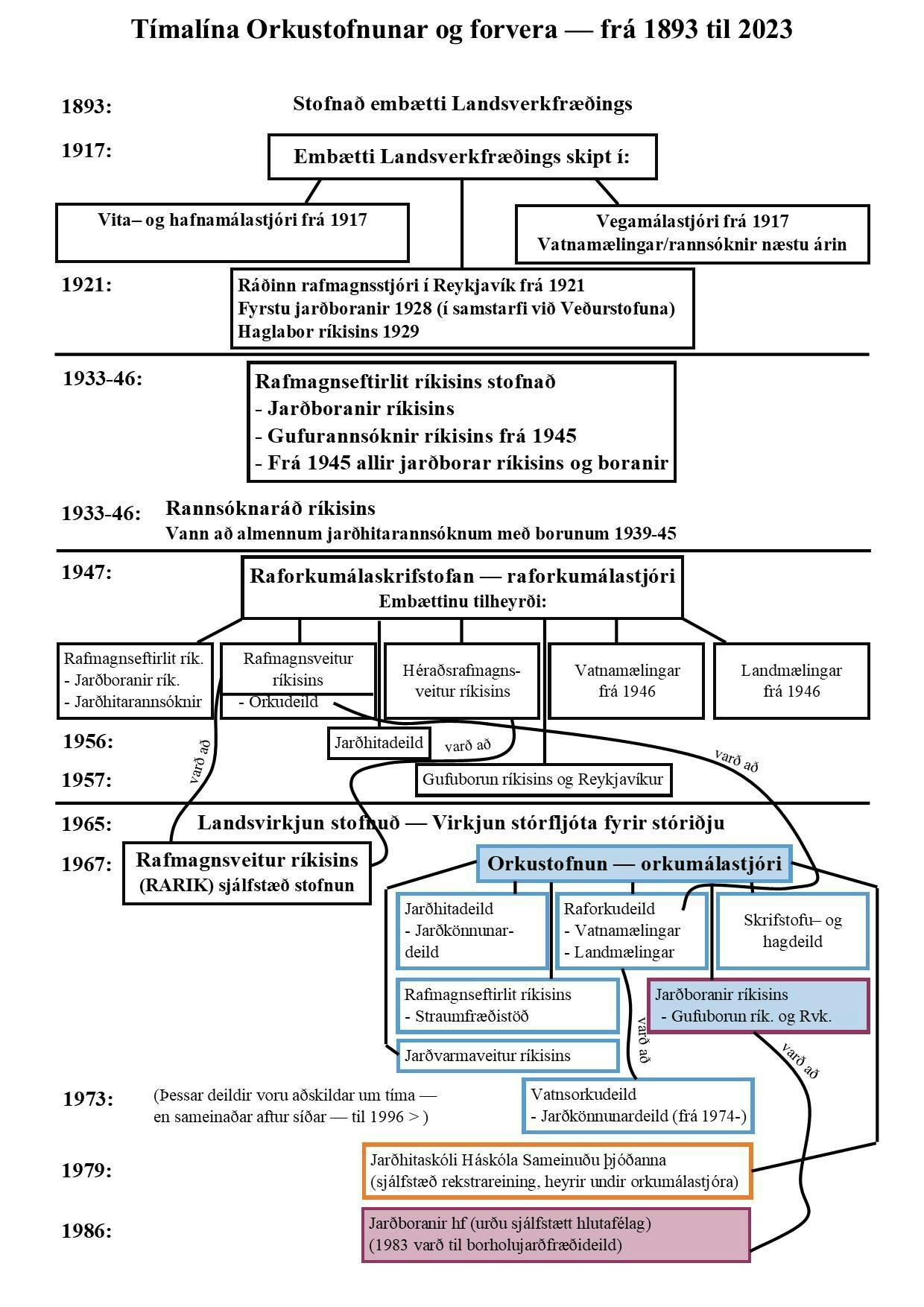

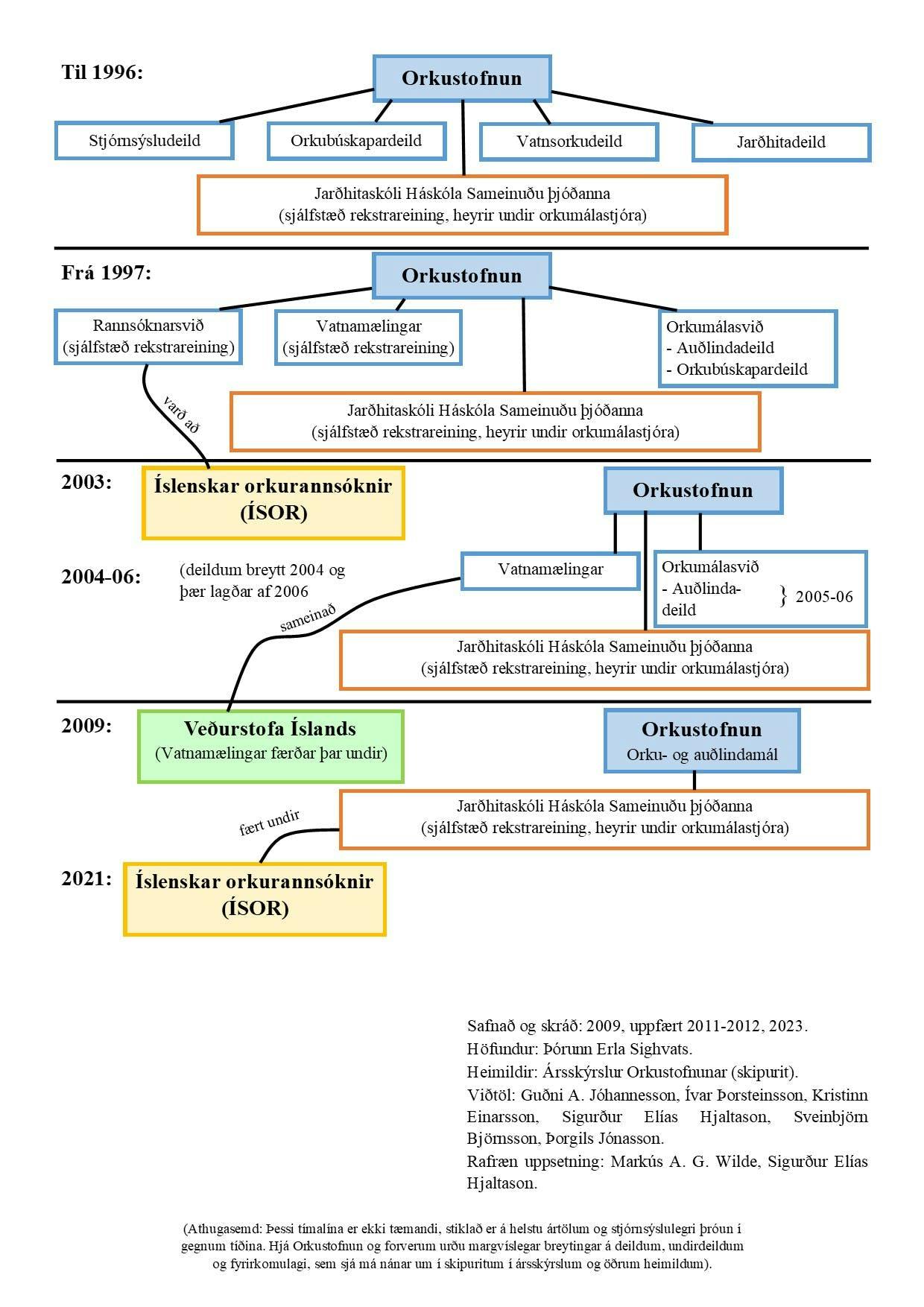

Timeline of Orkustofnun